You should know by now that African economies are growing. Almost every continental analysis leads with impressive data: economic growth rates hover at an impressive 6%; combined GDP will hit $2.6-trillion by 2020; foreign direct investment is flocking in to areas that were once no-go zones for the average international investor. It’s a compelling, feel-good story – and it just might be true.

This week, the Institute for International Finance (IIF) issued its report on the state of sub-Saharan Africa. The IIF, while not well-known outside specialist circles, is one of the most influential financial bodies in the world. An association of over 450 of the world’s biggest banks and financial institutions, it does everything from in-depth research and analysis to negotiating, alongside the European Union, a solution to Greece’s debt crisis (not, so far, its most successful project).

After noting the high levels of interest in Africa from their members, they’ve added up the figures, crunched the numbers and reached a conclusion: the African growth story is no mirage. It’s the real thing.

“After emerging Asia, Africa is the fastest-growing region in today’s world,” said George Abed, head of the IIF’s Africa and Middle East division. “Many countries on the African continent have achieved great progress in stabilizing their economies and consolidating their rates of growth. What is remarkable about this outcome is that it has been achieved during a period of unprecedented global financial turbulence. There are challenges ahead for Africa, but the trend of solid growth of the past decade looks sustainable over the medium term.”

This announcement is a big deal. It tells more than 450 of the world’s richest organisations that Africa is a decent bet, that it’s a safe place to put their money. It has the potential, too, to be a self-fulfilling prophecy: confidence in Africa’s economic future will encourage investment in that future, which in turn improves the chances of that future being as rosy as predicted.

The IIF is guilty, however – and it is not alone in this – of making sweeping pronouncements based on the relative success of just a handful of countries. Drill into the details of their report, and it is revealed that its research focuses on just seven countries: Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia, which together account for 65% of Africa’s economy. Since 2007, the seven have achieved a growth rate of 4.7%, which balloons to 6.5% as soon as South Africa’s grim decline is removed from the equation.

It’s an interesting mix of countries. South Africa and Ghana are considered models of democracy compared to their continental peers, and both enjoy significant resource wealth (South Africa in minerals, of course, and Ghana with its new-found oil). Nigeria is the most populous country, but is marred by the vices that so badly stunted Africa’s growth in the 20th century: corruption, mismanagement and poor governance. Tanzania and Zambia are both poor countries showing tentative but encouraging signs of economic and political stabilization. Kenya and Cote D’Ivoire, meanwhile, have both experienced severe conflict in the last few years and unstable governments; despite this, Kenya boasts one of Africa’s most dynamic economies.

It’s a small sample, but it is a good one and relatively representative of Africa as a whole: there’s good government and bad, there’s stability and conflict, there’s poverty and great resource wealth. Maybe it is Africa’s time after all.

This emerging positive narrative is doing a lot to change negative perceptions around doing business in Africa – which, in its own right, has hampered outside investment in Africa’s growth.

This is illustrated in another report released this year, Ernst & Young’s Attractiveness Survey, which found that Africa’s dubious reputation precedes it among big investors and corporations. “While awareness of its qualities is generally improving, Africa is still viewed as a relatively unattractive investment destination compared to most other geographical regions,” the report said. “Those already doing business on the continent were overwhelmingly positive, ranking Africa’s relative attractiveness above every other region except Asia (and even then, only marginally so). In stark contrast, respondents with no business presence in Africa were overwhelmingly negative.…This represents not so much a gap, as a chasm between perception and reality. The facts tell a different story — one of reform, progress and growth.”

It is this story that investors are increasingly buying into. South Africa, despite its sluggish growth, remains the favourite destination for foreign money. In 2011, for example, South Africa hoovered up nearly half of the estimated $12.5-billion in foreign direct investment aimed at sub-Saharan Africa. This overall figure is growing, to the tune of billions every year.

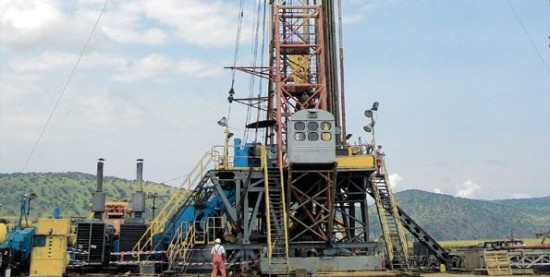

A few warning notes should be sounded, however. It’s never all good news. There are legitimate concerns that the African growth story is not sustainable, because it is reliant on an extended resource boom that can’t last forever. It’s also true that the numbers are skewed by big oil countries like Angola and Nigeria; take these countries away, and it’s likely the statistics would look very different – and not nearly so encouraging. Still, with some valuable resource being discovered in a new African country seemingly every few months (oil in Kenya, for example, or natural gas in Tanzania) there’s still life in the resource boom – and time for African leaders to use the money to create more reliable industries (unlike Nigeria, which declared last week that it had squandered upwards of $35 billion of oil money in mismanagement and bad practice).